Stories about the impact of new thinkers, installed on the walls of KTN’s head office in Islington.

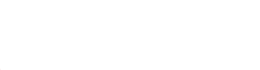

Michael Faraday (1791-1867)

“One of the greatest scientific discoverers of all time”

Today’s digital revolution owes much to Michael Faraday’s 1821 development of a motor using electromagnetic rotation, which led to electricity becoming practical for use in technology.

Faraday had little formal education, yet became one of the most influential scientists in history. As a chemist, he invented a forerunner of the Bunsen burner, discovered benzene and popularised many scientific terms that are widely used today.

But Faraday’s greatest impact was in the fields of electricity and magnetism, including the discovery of electromagnetic induction, diamagnetism, electrolysis and the models underpinning the electromechanical devices that powered the industrial revolution.

Faraday was a devout Christian and declined to advise on the development of chemical weapons for use in the Crimean War on ethical grounds.

Ada Lovelace (1815-1852)

The first computer programmer

The only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron, Ada Lovelace described her approach to mathematics as “poetical science” and herself as an “analyst (and metaphysician)”. She worked alongside her friend Charles Babbage and in 1843 produced a set of ‘Notes’ to her translation of the Italian Luigi Menabrea’s article about Babbage’s Analytical Engine.

It is Lovelace’s Notes that had the lasting impact. In specifying an algorithm to be carried out by a machine, many today view this as the first ever computer programme.

Where others, including Babbage, focused on calculation and number-processing, Lovelace saw that computers could go much further: she examined how individuals and society could relate to technology as a collaborative tool.

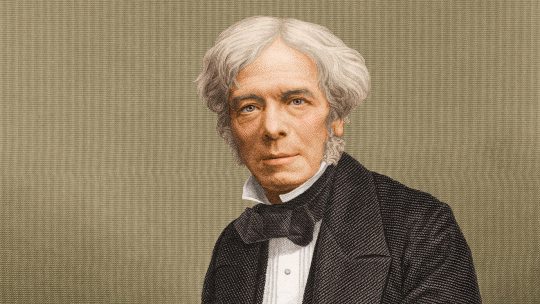

Frank Whittle (1907-1996)

Inventor of the turbojet

Flying and engineering were passions from an early age for Frank Whittle, who was admitted to the RAF at the second attempt and did so well as an engineering apprentice at Cranwell that he gained promotion to become an officer pilot.

Whittle developed the concept for a turbojet engine during his training, taking out a patent in 1930, and was admitted to Cambridge University where he gained a first-class honours degree.

In 1935, lacking the £5 needed to renew it, Whittle allowed his patent to lapse, but in the same year he persuaded hesitant investors to fund development with a concise explanation of his concept:

“Reciprocating engines are exhausted. They have hundreds of parts jerking to and fro, and they cannot be made more powerful without becoming too complicated. The engine of the future must produce 2,000 hp with one moving part: a spinning turbine and compressor.”

Whittle received a knighthood in 1948 and later emigrated to America, becoming a research professor at the US Naval Academy.

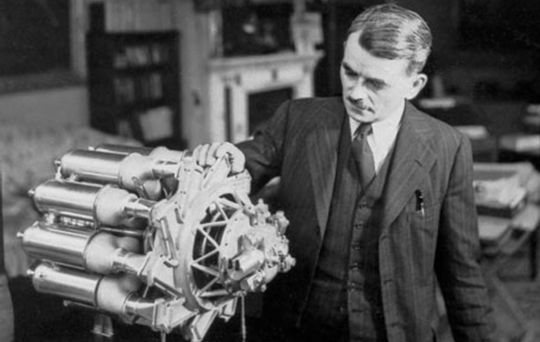

Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904)

Pioneer in motion pictures

The English photographer Eadweard Muybridge became world famous with large-format images of Yosemite Valley in the 1860s, but it was his work in moving image and projection that has had an influence on film, animation and special effects that endures to this day.

In the 1870s, Muybridge used time-lapse photography to document the construction of the San Francisco Mint and conducted multi-camera studies of running horses that changed our understanding of animal motion. In 1878, he created a 360o panorama of San Francisco that survives today as a stunning virtual reality experience. He went on to make many thousands of images capturing and representing human and animal motion.

Muybridge also developed the zoopraxiscope, a movie projector that predated the perforated filmstrip projectors of the early movie era. The hall he built for his presentation of moving images at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 was the first commercial movie theatre.

Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope projector along with thousands of prints and artefacts can be seen at the Museum and History Centre in Kingston-upon-Thames.

Florence Nightingale (1820-1910)

Pioneer in statistics and data visualisation

Many people know Florence Nightingale as the Lady of the Lamp in the Crimean War and founder of the world’s first secular nursing college at St. Thomas’ Hospital, London. Less well known is that she was a leading statistician and pioneer in the visual presentation of information and statistical graphics.

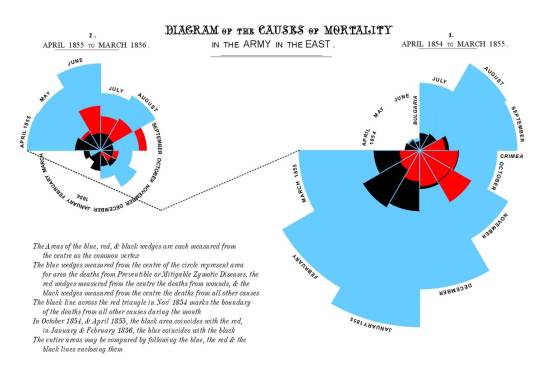

Nightingale used charts and diagrams to communicate complex medical information to policymakers and lay audiences. She developed the Nightingale rose diagram (above), a forerunner of the histograms in use today, to illustrate seasonal causes of death in a military field hospital, enabling appropriate preventive measures to be taken.

Nightingale’s investigation into the effects of poor sanitation on the health of British army personnel in India led her to look at the population as a whole and she instigated a Royal Commission to look into the problem. Her comprehensive statistical study of sanitation in Indian rural life made her the most significant figure in improving public health in India in the period.

Edward Jenner (1749-1823)

The father of immunology

Edward Jenner, creator of the world’s first vaccine, is said to have saved more lives through his work than anyone else. In the 18th century smallpox was widespread, killing eight out of ten children who caught the disease.

In 1796, testing the countryside folklore that milkmaids never caught smallpox, Jenner injected pus from the blisters on a milkmaid’s hand into the arm of eight-year-old James Phipps. This proved that contracting the relatively harmless cowpox provided immunity against the killer disease. Jenner quickly saw that vaccination could annihilate smallpox, which he called “the most dreadful scourge of the human species”.

It was another 44 years before the UK Government provided free vaccination, and a further century passed before Jenner’s solution was taken up worldwide.

George Daniels (1926-2011)

The world’s finest watchmaker

George Daniels’ mission as a horologist was to redesign the mechanical watch to compete and in the long term outperform the quartz electronic watch. He was passionate about every detail of watchmaking and, unusually, built complete watches, including case and dial, by hand.

Daniels watches were never made to order: all started life as a vehicle for testing escapements or some other idea to further the art of the mechanical timekeeper.

His greatest achievement was the invention of a movement known as “coaxial escapement”, which removed the need for lubricant in watch mechanisms and is seen as the greatest advance in mechanical escapement design since Thomas Mudge invented the lever escapement in 1754. Daniels’ escapement has been used in Omega’s top grade watches since 1999.

George Daniels’ contribution stands as a shining example of innovation in traditional craft by demonstrating the enduring value and quality of mechanical watchmaking.