Living Cities, a display of works from the Collection in the George Economou Gallery on level 4 of The Switch House, curated by Ann Coxon. Above: Peter Saville’s logo for the newly expanded Tate Modern, 2016.

It could be said the Living Cities display at Tate Modern is self-referential, because where other than in a cultural world city would this experience be found? It’s not Living Cities that is drawing in the crowds: the Switch House, Herzog & de Meuron’s extension to London’s temple of contemporary art, is the hottest ticket in town. This week, even before the new extension opened to the public, the gallery itself was the show.

Only members were admitted on several preview days, but queues of that privileged community were snaking around Bankside and the Switch House was teeming inside. The displays are like an interior designer’s carefully chosen objects by which the showflat is judged. Is Louise Bourgeois fabulous? Yes, but isn’t this a great way to appreciate her work?

This image of the environment as an actor, not a backdrop, in the experience of art has been at the core of Tate Modern’s identity since it opened – and explains its unpredicted success. “There’s no experience better,” says Nicholas Serota commenting on the new space, “than standing in a room with a group of works of art, helping them look as good as they can and to tell a story about their relationships.” And since architects Herzog & de Meuron feel this power as keenly as Serota, the Switch House – like the familiar but rebranded Boiler House next door – promises plenty of such experiences to come. The image of fashionably-attired folk of all ages sitting on and walking across Marwan Rechmaoui’s giant rubber map of Beirut is just so Tate.

Beirut Caoutchouc 2004-8 by Marwan Rechmaoui, embossed in rubber.

Not that the building’s celebrity status reduces the significance of the art. Living Cities may be a little overawed by having to share Level 4 with the great Louise Bourgeois as well as the magnificent bridge between Switch House and Boiler House, overlooking the Turbine Hall, but it is an interesting and thought-provoking presentation.

What would you expect of a display with that name? Cities by their nature change. Even dead cities – Nineveh, Pompei, Shicheng – fascinate only by the stories they tell about their living past. We may look at images of streets and stations and buildings, but their meaning lies in the life that goes on within. The Living City is a tautology. As Michael Batty puts it in The New Science of Cities (MIT Press, 2013): “Instead of thinking about cities as spaces, places, locations, we need to think of them as actions, interactions and transactions.”

The Tate’s description makes no attempt at definition, stating merely that the artists “explore differences between the cities in which they find themselves,” and “the artworks range from panoramic overviews to close-up images recording the minutiae of daily life.” Thus, uninhibited by a title that precludes pretty much anything at all, the display is left to ask its own questions, visitors to form their own conclusions.

Untitled (Ghardaïa) 2009 by Kader Attia. Cooked couscous on wooden table and digital prints on paper.

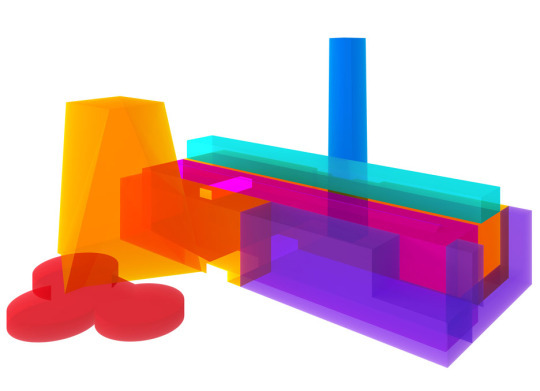

Kader Attia’s sculpting of the ancient Algerian city of Ghardaïa entirely out of couscous speaks of shapes and materiality, but equally of consumption and impermanence. Rechmaoui’s rubber Beirut focuses on the physical realm, but we can traverse it and wonder about the complexity and tragedy of that war-torn city, once the jewel of the Levant. Cairo, Addis Ababa and New York are characters in the tale of communal resistance that is Julie Mehretu’s Mogamma. Los Moscos is San Francisco slang for migrant labourers; the magnificent collage of that title by LA artist Mark Bradford is made up of random paper fragments combining into a living map of networks and connections.

Mogamma, A Painting in Four Parts: Part 3, 2012 by Julie Mehretu, Ink and acrylic paint on canvas.

Los Moscos 2004, mixed media on canvas, by Mark Bradford.

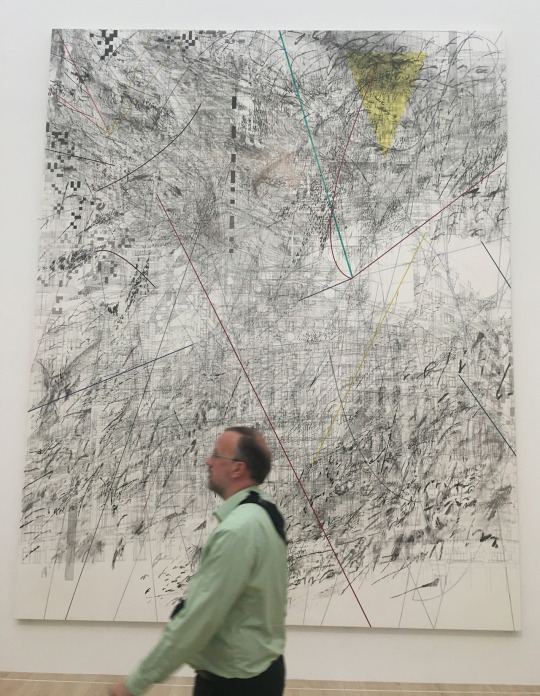

If these works seem to nod to the ‘Cities’ element of the narrative, Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen’s stark, haunting images of Newcastle’s Byker estate in the 1970s start firmly at the ‘Living’ end of the scale, speaking of the hardship, beauty and emotion of urban life with an urgency and pathos that only black-and-white photographs can.

Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, clockwise from top left: Kendal Street (Byker) 1969, Living Room Wall of Sidney Aubrey (Byker) 1975, Kids with Collected Junk near Byker Bridge (Byker) 1971, Jean Barron with Parents (Byker) 1980.

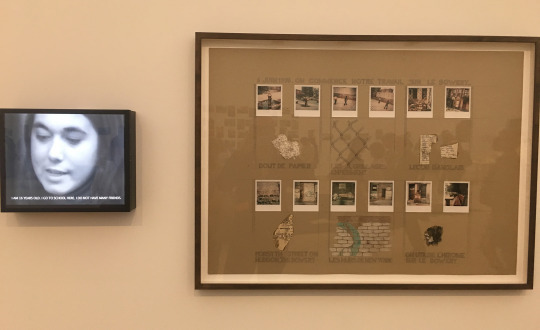

Nil Yalter’s Temporary Dwellings is on the same side of the argument, capturing transience and cohabiting cultures across international metropolitan cities – Istanbul, Paris and New York – with family life and loneliness in densely populated places: “I am 16 years old. I go to school here. I do not have many friends.”

Nil Yalter, Temporary Dwellings 1974-7, works on board and video.

Yet both tell stories in which the city is an important character. Boris Mikhailov’s Red series arguably goes right to the edge, with images of life in his home city of Kharkov. At first sight the city-ness of these images is less pronounced and the culture they portray was likely very similar in non-urban settings of the period. Mikhailov’s comment is on a social construct that in communist Ukraine was possibly more pertinent than the city: the Soviet.

Red 1968-75, 84 colour photographs, digital print on paper by Boris Mikhailov.

But that is the great thing about cities. All human life, even farming, takes place there in concentrated and accelerated form, so nothing is out of bounds. Cities have always been a subject of endless fascination – and that’s only increasing with the rate of urbanisation and more than half the world’s population now living in cities.

What this selection from the Tate Collection does is explore the agency and personality of our environment in who we are. We like to imbue inanimate spaces with human characteristics and behaviour – our cities to be living and smart, legible and tolerant. We know the environment is an actor and not just a backdrop. We want our public places to relate and interact, to entertain and above all to understand. It’s all so very Tate, and that’s what makes it great.

Central to this relationship at Tate Modern is the work of designers across multiple disciplines – architects Herzog & de Meuron, communication and exhibition designers Wolff Olins and Micha Weidmann Studios, wayfinding and signage designers Cartlidge Levene and Holmes Wood, iconic image designer Peter Saville, among many many more – all working collaboratively to deliver the impressively connected and coherent whole that is such an big factor in the success of Tate and its relationship with its visitors. This says much for the designers – and for the Tate’s vision and sophistication as a client.

When Herzog & de Meuron dug out the Turbine Hall to create the vastness of space that has delivered so much enjoyment and engagement in the last 16 years, they produced a new egalitarian democracy of space, a sense of ownership on the part of the visitor that engenders seamless and natural participation, one that contrasts with the Victorian pedestals of culture such as the Victoria & Albert and Tate Britain. This time, they say, “the oil tanks form the foundation of the building as the new volume develops and rises out of the structure below.” The tanks “are not merely the physical foundation of the new building, but also the starting point for intellectual and curatorial approaches which have changed to meet the needs of a contemporary museum at the beginning of the 21st century” resulting in a flexible range of large and small galleries alongside quirky ‘As Found’ spaces and plentiful facilities for the burgeoning membership and the popular learning programmes.

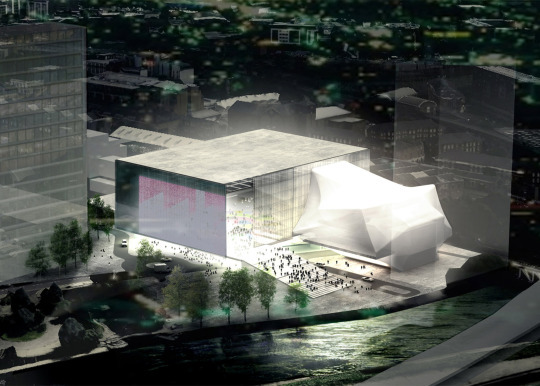

The spirit of democratic cultural space is rooted in European modernism and extended by digital: experiential, virtual, augmented, immersive, interactive. Rotterdam’s Kunsthal, designed by Rem Koolhaas and opened in 1992, has that ethic, reflected equally in Koolhaas’ concept designs for the iconic Factory arts centre, due to start construction in Manchester early next year.

Concept visual by Rem Koolhaas / OMA for The Factory arts and cultural centre at St John’s, Manchester.

These spaces tell stories about the image and usability of cities, in ways that are indicative of their wider attitude to openness, diversity, citizenship and participation: about whose cities they are. The questions asked of the modern living city are about our relationship with space and its role as an actor in our experience.

Malcolm Garrett’s logo for The Sharp Project in Manchester, 2010.

The building-as-actor was eloquently expressed in the identity design by that other iconic Manchester designer, my creative partner Malcolm Garrett, for The Sharp Project – the digital content hub described by the FT as Silicon Valley with chips and gravy, whose redevelopment by Alistair Weir of PRP Architects shares many of those egalitarian and ‘As Found’ characteristics.

Peter Saville’s elegant 3D development of that thought for the newly expanded Tate Modern takes a step forward to building-as-star, which, undoubtedly, it is.